I’ve just finished reading David Browne’s ‘Fire and Rain’, a lengthy volume which attempts to explain many aspects of why the 1960’s Hippie Dream turned sour and does so by concentrating on one year – 1970 – and on 4 groups or artists for whom 1970 was a big year; Simon & Garfunkel, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, The Beatles and James Taylor.

All 4 released albums in 1970 – Simon & Garfunkel’s ‘Bridge over troubled water‘, CSNY’s ‘Déjà Vu ‘, James Taylor’s ‘Sweet Baby James’ and The Beatles’ ‘Let it be’. Each of those albums were important inasmuch as they signified the end of the road for both The Beatles and Simon & Garfunkel, whilst ‘Déjà Vu‘ demonstrated how the addition of Neil Young to the mix completely destroyed the huge promise of the first ‘Crosby, Stills & Nash’ album from the previous year. With hindsight, only James Taylor’s ‘Sweet Baby James’ can be seen in a positive light; after all, it was the template for Taylor’s hugely successful career which still endures to this day.

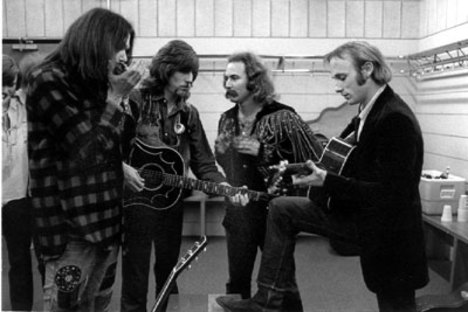

CSNY in 1970 – falling apart before they ever really got together

CSNY in 1970 – falling apart before they ever really got together

All of these albums – particularly ‘Bridge over troubled water’ – were highly successful in terms of sales but all except for the Taylor album are freighted with negative connotations.

Simon & Garfunkel’s final album was patchy. The title track was a monster hit everywhere and became an instant ‘standard’ and there were other fine moments like the quirky ‘So long Frank Lloyd Wright’, but there were some patchy moments as well. Overall, the album lacked the homogeneity of 1968’s ‘Bookends’ and, as Browne points out, many of the tracks featured either Garfunkel’s voice or Simon’s – there weren’t many moments where we were treated to the sweet joint harmonies of yesteryear.

‘Let it be‘ was a ragbag mess of a record after the smooth fluidity of its predecessor, ‘Abbey Road’. Few of the songs were of a quality that matched The Beatles’ achievements at their ‘Revolver’/’Sgt Pepper‘ peak. ‘Let it be’ revealed a band falling apart. The only surprise is that it was released at all; few other bands would have got away with it.

‘Déjà Vu‘ and the US concert tour that followed it turned Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young into the world’s biggest band by the summer of 1970. Yet the record – like the band – is deeply flawed, lacking the unity of mood, purpose and underlying philosophy which made the 1969 ‘Crosby, Stills & Nash‘ album one of the finest début albums of all time. By contrast, ‘Déjà Vu’ sounds like the work of 4 solo artists, which as Browne’s book reveals was pretty much the case. Only Crosby’s hippie potboiler ‘Almost cut my hair’ avoids this label as he insisted the whole band record it live in the studio. Looking back, it’s clear that Young only joined the CSN collective in order to further his own solo career. It’s of some significance that Young’s ‘After the Goldrush’, another 1970 release, leaves ‘Déjà Vu’ standing – and I say this as someone for whom Neil Young’s lengthy solo career is largely a monument to self-indulgence and tedium. All in all, it has to be said that whilst ‘Déjà Vu’ has its moments – Stills’ ‘Carry On’ and Crosby’s title track maintain the quality of the first album – the rest is pretty forgettable.

So, for Browne’s chosen artistes, we have two bands who disintegrated in 1970 plus one who were hardly together at all and all of this came in the wake of the Woodstock dream being soured by the events at the Altamont Speedway at the end of 1969. Even for Taylor, who was well on his way to becoming a major artist by the end of 1970, success was curdled by lengthy episodes of drug abuse and flirtations with the mental instability that informed some of his lyrics. All in all, it’s not a pretty picture, but the thing is, it’s also a distorted one, because in many other ways, 1970 was a time of harvest for many of the bands and performers who had been developing their music over the previous few years.

Even a perfunctory glance at a list of the albums that were released in 1970 show an extraordinary diversity and range of talent. This was the year of Van Morrison’s ‘Moondance’ , of Santana’s ‘Abraxas’, of Pink Floyd’s ‘Atom Heart Mother’, Traffic’s ‘John Barleycorn must die’ and Joni Mitchell’s ‘Ladies of the Canyon’. How different, how much more positive could Browne’s story have been if he’d chosen these albums and artists instead of the ones already mentioned?

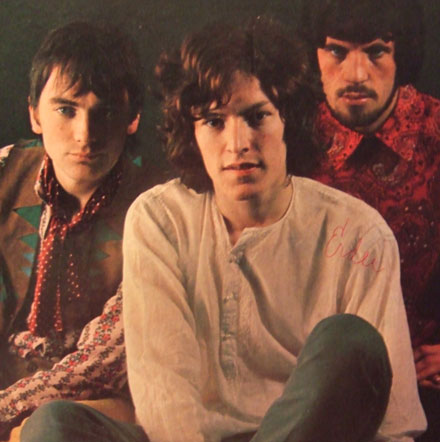

Traffic in 1970; (L-R) Wood, Winwood & Capaldi

Traffic in 1970; (L-R) Wood, Winwood & Capaldi

Well, of course, Browne chose the artists and albums he did because they illustrated the specific point he was trying to make about the death of 1960’s idealism and the encroachment of greed, ego and narcotics upon the hippie heartlands of yesteryear. To be honest, his points are well-made, but I have to ask myself which of the artists he covered were on my personal ‘playlist’ in 1970. Maybe ‘Déjà Vu‘ – though I usually reverted to the first ‘CSN’

album by preference – and from time to time later on in the year, Taylor’s ‘Sweet Baby James’ once it strayed across my radar. The other two were not albums I listened to at all – I always felt that ‘Let it be‘ was rubbish aside from a couple of the tracks and I found ‘Bridge over troubled water‘ too syrupy and bland. Some people found the title track magnificent; I just found it overblown.

I’ve already mentioned a few of the top albums released in 1970 – here’s a more comprehensive list:

Derek & the Dominos – ‘Layla and other assorted love songs’

The Mothers of Invention – ‘Burnt Weeny Sandwich’ / ‘Chunga’s Revenge’

Free – ‘Fire & Water’/’Highway’

George Harrison – ‘All things must pass’

Grateful Dead – ‘Workingman’s Dead’ / ‘American Beauty’

Jimmy Webb – ‘Words & Music’

Joni Mitchell – ‘Ladies of the Canyon’

King Crimson – ‘In the wake of Poseidon’ / ‘Lizard’

Led Zeppelin – ‘III’

Neil Young – ‘After the Goldrush’

Pink Floyd – ‘Atom Heart Mother’

Rod Stewart – ‘Gasoline Alley’

Ry Cooder – ‘Ry Cooder’

Santana – ‘Abraxas’

Soft Machine – ‘Third’

Supertramp – First Album (‘Supertramp’)

Allman Brothers Band – ‘Idlewild South’

The Band – ‘Stage Fright’

The Byrds – ‘Untitled’

The Doors – ‘Morrison Hotel’

The Rolling Stones – ‘Get yer ya-ya’s out’

Todd Rundgren – ‘Runt’

Traffic – ‘John Barleycorn must die’

Yes – ‘Time and a Word’

Family – A Song for Me’

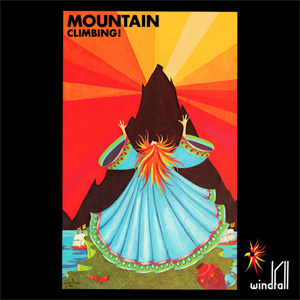

Mountain – Climbing!

Egg – ‘Egg’

Miles Davis – ‘Bitches’ Brew’

The Flying Burrito Brothers – ‘Burrito Deluxe’

Country Joe and the Fish – ‘C.J. Fish.’

Blodwyn Pig – ‘Getting to this’

The Who – ‘Live at Leeds’

Ginger Baker’s Air Force – First Album

Dave Mason – ‘Alone Together’

Fotheringay – First Album (‘Fotheringay’)

Quicksilver Messenger Service – ‘Just for Love’ / ‘What about me?’

Nick Drake – ‘Bryter Later’

Tim Buckley – ‘Starsailor’

Spirit – ‘The 12 Dreams of Dr Sardonicus’

Roy Harper – ‘Flat Baroque & Berserk’

If – First Album & ‘If 2’

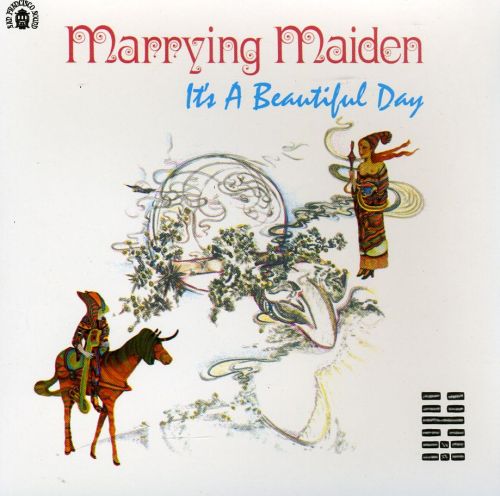

It’s a Beautiful Day – ‘Marrying Maiden’

John McLaughlin – ‘My Goal’s Beyond’

Quintessence – ‘Quintessence ‘ (Second album)

John & Beverley Martyn – ‘The Road to Ruin’

OK, so here are close to 50 LP’s which also saw the light of day in 1970 and might paint a rather less negative picture than Browne offers in his book. People often talk of 1967 as being the magical year for music but for me, 1970 is the year that really counts. You can make your own mind up about that.

After this, of course, there was Bowie and The Eagles and Little Feat and Steely Dan – overall, something new. Whilst the 60’s was a fading dream , the 70’s offered something different. 1970 was a year that marked the dividing line between the two decades and gave us a whole new set of possibilities.