After the social whirl of March’s Sri Lanka extravaganza, the end of April saw me embarked on a solo outing to the place where the new Europe and the old one overlap – Berlin – with onward connections to Poland and the journey I have wanted to make for many, many years now, to Krakow, Auschwitz and Mitteleuropa’s particular ‘heart of darkness’.

Travelling alone is something I used to do a lot of back in the days when I used to work in the travel biz; I would be tasked with checking out a particular area of (usually) Scandinavia and would meet with hoteliers, transport companies and the like, whilst investigating potential attractions to be woven into a 7-, 10- or 14 day programme that could be incorporated into the following year’s brochures – ‘Finnish Panorama’, ‘Land of the Midnight Sun’ etc ; you get the general drift.

However, the thing is that although I travelled alone between destinations, I always had people to meet and appointments to keep once I got to wherever I was headed. With this trip, the only schedule was the one I decided on and with flights, trains, hotels and suchlike all booked in advance, I simply had to show up and meander through my own self-devised itinerary, visiting the sights and hitting the hotspots that interested me. Deciding where to have dinner was sometimes the only real variable in my day and having always been comfortable in my own skin, the prospect of wandering round central Europe on my own didn’t bother me that much, but I suspect I underestimated the impact of a programme with such a minimal level of social contact built in. Certainly, I didn’t take into account the emotional impact of some of what I would experience.

One of the images from the East Side Gallery in Berlin

It wasn’t even that this was a trip that I wanted to do alone and with the benefit of hindsight , I wish I’d worked a little harder to find a travelling companion or two. It’s just a simple fact that most of my family and friends are caught up in a cocktail of work or financial or (even) grand-parenting issues that would have made it impossible for them to join me for one or more reasons. However, the thing that really drove me out the door on this occasion was news of the imminent arrival of an Aussie friend of the Partner’s – let’s call her Matilda – whose mere presence is enough to inspire paroxysms of mild nausea and loathing in me – I have my reasons, believe me. Matilda and her ex-husband were part of the social flotsam and jetsam with which the Partner chose to populate her life in her free & easy late 20’s. Most of this lot have now thankfully disappeared into the mists of history, but not Matilda, who although she lives in Perth, waltzes into Europe far too frequently for my liking.

When this happens, I take the view that it’s better and simpler for everyone if I just get out of Dodge. Normally, I might visit mates in Shropshire or Derby, but on this occasion, I decided to make a virtue out of what I perceived to be a necessity and orchestrated a week-long trip to Berlin and Krakow. This did not meet with universal approval; the Partner’s attitude combining anger at my ongoing disdain for her Aussie friend and irritation that I am able to just clear off for a week at the drop of a hat when she is still shackled to the workplace.

Predictably, all of this domestic sturm und drang came floating to the surface like so much unwelcome scum the night before my departure, by which point it was in any case far too late for me to do anything about it – even if I’d cared to. Under the circumstances, I guess I can only take pride in my unwavering knack for consistently locating that ‘sour spot’ that exists somewhere between ‘deeply flawed’ and ‘completely wrong’. Sad but true, folks; I’m reliably and regularly informed that I’m no angel and having been told this for well over 20 years, I guess it must be true.

And so to Berlin, where the sun was fighting to get through a grey blanket of cloud and I was soon fighting to get to grips with the highly-touted public transport system. Airport Bus to some place the other side of Tiergarten, then U-Bahn (or was it S-Bahn – and what’s the difference anyway?) to Potsdamer Platz with its glass towers and forest of pink piping and a tedious walk down the road to my hotel; a clean functional Ibis with staff who were efficient and friendly in that impersonal corporate manner we are all supposed to applaud.

There was enough of the afternoon left for me to explore my immediate surroundings, which were, specifically, the area between Potsdamer Platz and Kreuzberg. This is an area of no great architectural merit with only the remaining section of the facade of the old Anhalter Banhof and the soaring white spires of the Tempodrom concert hall to enliven things. In the end I wandered up to Potsdamer Platz to photograph the pink piping – there to pump away ground water as Berlin apparently has a very high water table.

Pink pipes in Potsdamer Platz

Later, I walked down into Kreuzberg and had a pleasant dinner at a Nepalese/Tibetan restaurant called ‘Tibet Haus’, recommended to me by the Princess; another of the sundry weirdnesses connected with this excursion was that all 3 members of this household have now visited Berlin within the last 2 years, but we have all done the trip independently of one another. Did I hear somebody say ‘dysfunctional’?

I didn’t anticipate leading a wild nocturnal existence on this trip, but I did check out a few Berlin websites to see if there were any gigs or exhibitions I could go to during my stay. It was a pleasure to find that promising young Norwegian nu-jazz trio, In the Country, were playing at a jazz club called A-Trane across to the west of the city in Charlottenburg, so after my Nepalese curry I cabbed over to A-Trane to see them play. And what a delight that turned out to be!

In the Country

Pianist Morten Qvenild has the highest profile due to his role as ‘the Magical Orchestra’ behind Susanna (Wallumrød), but In the Country have been active for 8 years now and are touring around their fifth album, ‘Sunset Sunrise‘, so-called because they recorded it at Los Angeles’ famous Sunset Sound last summer during a few days downtime whilst on tour in the States. Qvenild has also been involved with other Norwegian nu-jazz bands like Shining and even an early incarnation of Jaga Jazzist. He gets great support from drummer Pål Hausken and bassist Roger Arntzen and there’s never any suggestion that this is merely Qvenild’s band. To some extent, they have taken ideas originally explored by the Esbjörn Svensson Trio; notably the discreet usage of synthesiser, electronics and vocals to boost the basic trio sound – and they do it brilliantly.

They played 2 marvellous sets to a pretty packed club and I cabbed home some time after 1 am feeling happy with my first day.

For the next 3 days, I went into full tourist mode, wandering the city at some length and visiting sites that were obvious choices like Checkpoint Charlie, the Brandenburg Gate and the Reichstag plus others that were recommended to me like the DDR and Jewish Museums. The weather was pretty good and I got better at navigating my way around. I found a great Malaysian/Filipino restaurant called Mabuhay, located in the most unpromising of back street car parks with a Lidl supermarket next door – the food was good, though. I swiftly became very taken with Berlin’s quirky feel and tried to preserve enough energy to explore areas like Kreuzberg and Prenzlauer Berg. On Bergmannstrasse, I ate the best wienerschnitzel I have ever had but had less positive experiences with the local wurst and kebab stalls.

If my experiences with the local cuisine were mixed, the same could definitely be said of the local history and politics, which gave me the same kind of unsettled feeling as that ill-chosen bratwurst I ate one lunchtime.

Even though the Wall is gone, its ghost dominates Berlin in so many ways and though Berlin’s location in the centre of Europe reveals a city that might look just as readily to the west as to the east, you sense that the shadow in the east predominates. The elegant avenues of Charlottenburg and the glitzy shops of Kurfürstendamm might wish to emulate Paris, but some of the grim concrete plazas around Alexanderplatz seem more representative of the city’s recent Stalinist past. War, whether cold or hot, is the dominant motif in the city’s geography and history – the further east you go the clearer that becomes. It’s really quite difficult to understand how West Berlin survived as an island of capitalist excess in East Germany’s grim backwaters, but it did for over 40 years and nowadays the U-bahn and S-bahn trains sweep through former ‘ghost stations’ like Bernauerstrasse with no indication of past problems. Above ground it’s a different story and the city makes the most of what the Wall left behind. Most notably, the East Side Gallery on Mühlenstrasse offers us 105 paintings along a 1.3 km long section of the Wall. These were painted in 1990 when euphoria levels about German reunification were still high, but many of the images now look tired and have been besmirched with mindless graffiti by people who really ought to have a bit more respect.

Detail from a section of Wall at the East Side Gallery

Further north in Prenzlauer Berg, a section of the ‘Death Strip’ between the East & West Walls has been maintained in its original configuration. Stretching between Nordbanhof and Bernauerstrasse stations, the site offers a memorial to those who died trying to get across as well as photographic records of how different the site looked at the height of the Cold War. Further north still is the Mauerparken – a strip park built along the line of the Wall where a huge flea market takes place every Sunday.

I wandered round the flea market, finding myself curiously unmoved by its bewildering variety of offerings, but other people were heading back along Bernauerstrasse with small cabinets, stuffed animals, metal tractor seats and the like. I took the U-bahn from Bernauerstrasse station and a guy came and sat next to me nursing a huge framed print of the worst kind of 1970’s sub-Pink Floyd ‘space art’. He looked very pleased with his purchase, but then again, hopefully he just wanted it for the frame .

The Mauerparken

The DDR Museum offered a wry thumbnail sketch of what life might have been like in the old East Germany but the Jewish Museum was a different matter altogether. Daniel Liebeskind’s design is deliberately intended to produce a disorientating and emotional effect with its angled floors and voids, to say nothing of the actual content of the exhibits. Let’s just say that with me it succeeded admirably. I have in the past visited both of London’s Jewish Museums and never found either of them as troubling. In the end, I became almost panic-stricken in trying to find a way out of the place. Here was all the evidence of a vibrant culture destroyed, here were the touchstones of a way of life that has been forever lost. In a very direct way, Berlin’s Jewish Museum was signposting my way to Auschwitz.

Inside Berlin’s Jewish Museum

The last site I visited on my final day in Berlin was in many ways the most troubling of all. To the south-east of the city centre, the Soviet War Memorial in Treptower Park is both a mass grave for the 80,000 Red Army soldiers who died in 1945’s climactic Battle of Berlin and a memorial to their sacrifice. The monument was built in 1949 and is rendered in the usual Soviet/Heroic fashion. It’s a huge site with- as its centrepiece – a 12m high statue of a Soviet soldier holding a child in his arms whilst lording it over the broken swastika at his feet.

Whatever my feelings about the vanished world of Soviet Russia, there is no doubting the suffering that country underwent at the hands of the Nazi invaders during Operation Barbarossa and its successors. The Nazis saw the Slavs as being an inferior race suitable only as slave labour and they despoiled the towns, cities and local populations of the lands they conquered in Ukraine, Belarus and Poland. As the Russians headed west in late 1944, it was time for a little revenge and whilst Russian historians dispute this, there seems little doubt that the invading Red Army were responsible for massive reprisals against the German population as they drove westwards towards Berlin. In particular, Soviet soldiers are said to have been responsible for as many as 2 million cases of rape in Germany, with victims ranging from 8 to 80 years old. About 100,000 of these rapes were said to have occurred during the Battle for Berlin. So much for the heroic Soviet Army, but it seems that French, American and British soldiers were also getting in on the act as they invaded from the West, so to point the finger at the Russians alone would be hypocritical indeed.

The Soviet War Memorial at Treptower Park

I found this ‘credibility gap’ between the narrative of War as portrayed through its memorials and museums and the underlying stories of ordinary people whose suffering was on a different level altogether to be a recurring motif on this trip and the more I saw of it, the more disturbing I found it. The ‘grand narratives’ of generals and statesmen and war heroes don’t seem to make any sense here – the Jews of Berlin were reviled, ostracised, then dispossessed and exterminated, the heroic Red Army were not the liberators of myth, but simply an armed rabble who raped and pillaged their way through Poland and Eastern Germany until they met up with the Allies at the Elbe, the women of Berlin (many of them) paid a terrible price for Hitler’s racism. arrogance and deranged fascist ideologies…..what’s wrong with this picture?

Before this trip, I would have said that I knew quite a bit about all of this, having read a number of books about it and seen quite a few documentaries – certainly I felt that the blinkers were off as far as I was concerned, but I still found the growing gap between the official viewpoint and what ordinary people actually experienced somewhat alarming. More to the point, it was not something I had been able to discover through books or films, but something I picked up simply from wandering round Berlin’s monuments and museums. How much more of a shock would Poland prove to be?

I was soon to find out. The next morning I took a cab to Berlin’s magnificent glass and steel Hauptbanhof, opened in 2006 and one of my favourite modern structures. Anyway you look at it, it’s a magnificent building and must make arriving in Berlin by train a truly uplifting experience.

Berlin’s Hauptbanhof

However, I was leaving, not arriving and I boarded the 9:37 train to Warsaw and found myself sharing a compartment with a Russo-German family of 4 and a German girl in her 20’s who bore a disconcerting resemblance to my next-door neighbour. Ordinarily, I would have been able to travel directly to my final destination, Krakow, rather then go via Warsaw, but the track between Berlin and Krakow is apparently being upgraded to take high-speed trains, so a detour through central Poland to Warsaw was the first stage of a 10-hour journey. There was no small talk with my neighbours – the German girl was ploughing through a hefty John Irving novel and the Russo-German parents were busy with their infants. I played my iPod to shut out some of the noise and concentrated on the unravelling view outside the window. It’s only 50 miles from Berlin to the River Oder which forms the international boundary with Poland and an awful lot of that territory is covered with pine forest – planted rather than natural, I assume. Once across the river and into Poland, however, the landscape began to change to a gently undulating landscape of fields, copses and low hills. With the first flush of springtime green on the land, it looked incredibly attractive in a kind of ‘Nymphs & Shepherds come away‘ fashion. Given the ‘Volkish‘, back-to-nature ideologies of the Nazis, it’s easy to see the attraction of these bucolic landscapes with their gingerbread cottages and echoes of a simpler, nobler past, free from the corruption of the big cities with their Jewish predators waiting to pounce on simple Aryan country boys.

On the way to Warsaw, we passed through a number of provincial towns and one major city – Poznań – none of which looked particularly noteworthy. By 3 pm I had reached Warsaw Zachodnia station (formerly Warsaw West), a satellite station some miles from the centre of the city. Quite why I needed to change there rather than in the centre of the city is something I couldn’t explain to you. From the platforms at Zachodnia I had a good view of Warsaw’s central landmarks, notably the near-800 foot high Palace of Culture & Science, built between 1952 and 1955 and donated to the people of Poland by the people of the USSR. Locally, it’s sometimes referred to as Stalin’s Syringe and can be seen just left of centre in the picture below.

After some 45 minutes or so, my train to Krakow duly appeared and once aboard I settled back for another unravelling panorama of Polish farmlands outside my window. This express didn’t stop at all and after just over 3 hours we pulled into Krakow’s modern station. One overpriced cab ride later and I was at the Globetroter (with just one ‘t’) Guesthouse in the Old Town.

It was the 29th April when I arrived in Krakow. The most urgent question I had to answer was when to visit Auschwitz. Should I go the following day or have an easier day in Krakow? I was inclined to follow the latter course, but that would mean deferring my Auschwitz trip for a further day, which would mean trying to go there on 01 May, a well-established public holiday. I knew that the Museum itself would be open on May Day, but would getting there be a problem?

The (unpronounceable) modern town of Oswiecim is (depending on the route you take) just over 40 miles west of Krakow and because of the logistics of visiting the Auschwitz sites, an early start is essential if you wish to avoid the crowds and find your own way around the place. Essentially, if you arrive after 10 am, you are compelled to join a guided tour around the museum and this was something I was keen to avoid for a variety of reasons. For one thing, I am probably a bit too well-informed about the Nazis’ ‘Final Solution’ and wouldn’t really need to hear all the ‘back-story’. For another, I knew that this was likely to be my one and only visit to Auschwitz, so I wanted it to make sense for me and the only way that could happen would be for me to be in charge of my own itinerary, so to speak.

After popping out to a nearby restaurant, I returned to Globetroter to check out the weather forecast on BBC World. The 30th was set fair, but the 1st promised rain for Western Poland, so my decision was made for me.

I was in bed by about 9:15 pm, awake well before 6 the following morning and on my way to the Bus Station before 7. Once there, I managed to find a place on the 7:50 minibus, along with a ragbag collection of half-asleep tourists and young Poles on their way to work at intermediate stops along the way. The journey took about an hour and 20 minutes and we were eventually dropped off in a featureless suburban street on the outskirts of Oswiecim. A sign saying ‘Museum’ which led off down a footpath towards a fenced enclosure was the only clue to our whereabouts. Following this footpath, I soon found myself in the Museum’s main car park and was surprised to see how busy it was given that it was only about 9:15 am.

Entry to the Auschwitz site is free (as it should be) so I avoided a few groups that were gathering and simply walked through into the approach to the camp. First impressions were how small, compact and neat it looked – and then you spot the ‘Arbeit macht frei’ sign….. The word ‘iconic’ is overused these days, but there is no denying the power of that cynical piece of signage.

The gate into the Auschwitz 1 camp as you first see it

And then….just a few steps for a man, as Neil Armstrong might have said and you are inside. How easy it would have been for me to about face and walk out again and how many uncounted thousands would have liked to be able to do the same and yet could never do so? I don’t – as far as I know – have an iota of Jewish blood in me, but just stepping across that threshold made my WASP plasma run cold.

Auschwitz 1 is an unnerving place on numerous levels. Yet again I found myself assailed by those feelings of dislocation between the evidence before my eyes and the reality of what went on in this dreadful place. The original site was a way station or transit camp for migratory farm workers who every year travelled the roads of Bohemia, Moravia, Poland, Silesia and Germany in search of employment. Similarly, landowners would travel to Auschwitz in order to recruit labourers. If you look at a map, you will see that Auschwitz lies at the crossroads of Europe and well before the railways were built, the high roads from Berlin to Prague and from Krakow to Vienna passed nearby. Later it became a Polish army barracks and then the Nazis took over. The excellent communications links from Auschwitz to both east and west found favour with the architects of the ‘Final Solution’ and the proximity of the Silesian coalfields meant that big companies like I G Farben were prepared to open chemical factories there – resulting in Auschwitz 3 or Monowitz where Farben used inmates from the camps as workers.

Inside Auschwitz 1, the trees are showing new growth, the roads and walkways are tidy – the calm is eerie. Only when you look up to the wire and the watchtowers do you get a true sense of what this place was really about.

A number of the 20-odd barrack blocks have been converted – some for use as office space, others as homes for the site’s permanent exhibits and for individual national displays from Austria, Poland, the Czech Republic and so on. Knowing that a long and trying day lay ahead of me, I chose to focus on the permanent displays because it is really only here that the spick-and-span barracks are revealed as the houses of horror they really were. The exhibits that reveal Auschwitz’s true nature are those that focus on daily life within the camps and the way in which the incoming millions were exploited and abused by their captors.

I have often remarked to people that there are some ‘sights’ – the Taj Mahal, the Manhattan skyline and the Eiffel Tower are 3 that spring to mind – that retain their power to impress, even though you have inevitably seen them hundreds of thousands of times on TV and in books. For me, Auschwitz has a few of these and the first are the monstrous display cases full of human hair and suitcases and shoes in the barracks that deals with the Nazis ideas about ‘harvesting the dead’. Particularly grim is the case full of small shoes taken from the feet of innumerable dead children; the point is that all of this stuff is just a fraction of the total volume of such items generated during the life of Auschwitz and the other Nazi death camps.

Children’s shoes in the museum at Auschwitz 1.

I concluded my visit to Auschwitz 1 by visiting the ‘Punishment Block’ in Block 11 and the adjoining yard where the Nazis put at least 20,000 people up against the so-called ‘Black Wall’ and shot them. Inside Cell Block 11 were the basement cells where prisoners were often left to starve to death or forced to crawl into miniscule 4-person ‘standing cells’, so small that there was no possibility of the inmates being able to sit, let alone lie down. It was also in this basement in September of 1941 that the Nazis first trialled Zyklon B as a killing gas on 600 Soviet prisoners and 250 ill and injured prisoners in a makeshift gas chamber. The ‘Black Wall’ has been reconstructed in the sealed yard between Cell Blocks 10 & 11 and the windows of Block 10 that faced on to the yard shielded to prevent the inmates from seeing what was happening outside, though they could no doubt guess from the sound of gunfire. In any case, they had troubles of their own as Block 10 was where the infamous Josef Mengele carried out his barbaric medical experiments on twins, pregnant women and the like.

To be honest, I was shocked by the impact of all this on me; after all I knew most of this stuff, but it’s one thing to read about it or watch an elegantly-constructed BBC documentary or even Claude Lanzmann’s nine-hour epic film ‘Shoah’, but to be there and see these things in person just floored me.

Something else that floored me were some of the exhibits that dealt specifically with the role of the local population in the affairs of Auschwitz. We all know that Poland was over-run by both Soviet & Nazi armies during World War II and we know that the Nazis were responsible for the forced deportation of huge numbers of Poles to work as slave labour in the mines and factories of the Third Reich. What we also know is that whilst the Poles as a race were disinclined to collaborate with the Nazis, they were also largely indifferent to the fate of the (nearly) 4 million Jews living in their country at the start of the War. Despite all the fine talk of how few Poles actively collaborated with the Nazis, most Poles would probably argue that they had problems enough of their own without taking up the fight on behalf of the Jews. For all this, the spectre of Polish anti-Semitism hangs over some of the exhibits at Auschwitz 1, particularly those ‘visiting’ exhibitions (usually Polish-sponsored) that deal with Resistance to the Nazis and the way in which the Poles found common cause with Jews, Roma and other oppressed minorities. For me, a lot of this stuff just didn’t ring true. Apparently, the current Chief Rabbi of Poland is pleased that the percentage of Poles who harbour anti-Semitic feelings is now down to 45%. How high must it have been in the early 1940’s – a time, where if you believe some of the stuff I saw at Auschwitz, heroic Polish freedom fighters were finding common cause with their Jewish brothers to fight the shared Nazi enemy? No, I don’t believe it either….yet again, I found myself teetering on the brink of a credibility gap between the revisionist history that will make us all feel comfortable with one another in the 21st Century EU and the evidence of my own eyes and ears….and brain.

All of the horror of what had been done here, allied to the half-truths and reassuring balm that the Polish-born, Polish-trained multilingual guides were no doubt feeding into the headphones worn by the incoming groups of impressionable but subdued teenagers from Sweden and Italy and America…well, it all just caught up with me, frankly. 45% of Poles still have anti-Semitic views, despite the largest genocide of all time happening right on their doorstep. How bad would things have to have got before we could get that figure down to 25%? How many more millions would have to have died in the gas chambers?

Like Santayana said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”. Roll over Pol Pot and tell Rwanda the news…..

Of course, visiting Auschwitz without going on to the second camp at Birkenau is to surely miss the point completely. At Auschwitz 1, the victims were a mixture of Soviet Prisoners, Polish dissenters, Roma, homosexuals, political prisoners and so on. At Birkenau, it was really all about the Jews. From the car park outside Auschwitz 1, a free shuttle-bus will take you to Auschwitz 2/Birkenau. In geographical distance there is only a couple of miles between the camps, but conceptually, it’s a whole new ballgame.

The first thing that gets you is the sky, strangely enough – at Auschwitz 1 you are hemmed in by the red brick barracks and by trees – it’s all pretty claustrophobic. At Birkenau though, it’s a different story. Apart from the (here’s that word again) ‘iconic’ gatehouse which Lanzmann uses as a visual cueing device throughout ‘Shoah’, everything at Birkenau is low to the ground. Simply put, the site is huge, covering over 150 hectares (or 1.5 million square meters).

There were no existing buildings here so the Nazis threw up basic low barracks buildings – by 1945, there were 300 of them. Stretching away into the misty distance you can see the fingers of the stove chimneys for each barracks, all that remains of most of the barracks, though some have been rebuilt to show how terrible living conditions were at Birkenau. However, by the time Birkenau was up and running in 1942, the Nazis were much more concerned about dying conditions than living conditions. They had set themselves to exterminate the Jews of Europe and to do the job on an industrial scale. Birkenau was one of the death camps they set up in Poland in order to carry out this task.

The gatehouse at Birkenau – it still gives me chills….

The railway line that leads into Birkenau is a spur that the Nazis built to increase the efficiency of their Birkenau Death Factory. Jews could be unloaded directly on to the ‘Ramp’, divested of their possessions, split into male/female groups and assessed for their ability to work before being marched down the ramp to the delousing showers and their eventual doom.

It’s a long way from the gatehouse to the wreckage of the crematoria at the other end of the site but it’s a journey that everyone takes. I saw an extended family of Israelis, the children wrapped in Star of David flags, most of the adults weeping openly. They marched in line abreast back towards the gatehouse, towards freedom and a country that didn’t even exist when the Nazis set this place up in 1942. I can only wonder at the complexity and depth of their feelings..

I took that walk as well, down to the anticlimactic ‘International Monument’ and the brick and concrete wreckage of the Crematoria. Nearby on either side of the wreckage are small pools with gravestone-type memorials in front of them. A young girl sat in silence next to the southernmost pool. I wanted to say something to her but wouldn’t have known where to start.

The ‘undressing room’ at Crematorium II at Birkenau

By this point, I was shattered – both physically and emotionally. I trudged back to the gatehouse and picked up a return shuttlebus to Auschwitz 1, then picked up a minibus back to Krakow.

In the evening, I ventured out into the streets of Krakow’s Old Town and found a bar overlooking the enormous Market Square. I suppose I needed to talk to someone about all that I’d seen, but that was denied me. No friendly faces appeared and I probably looked extremely grumpy anyway. I had a beer and watched the world go by, then ate a perfunctory dinner before returning to the Globetroter to sleep. It had been enough of a day.

The following day was my final full day in Poland and I wanted to see as many of Krakow’s sights as I could. Based on what my guidebook was telling me I immediately set off for Wawel – a huge rock on a bend in the River Vistula to the immediate south of the Old Town where the original settlement of Krakow was set up. These days Wawel is dominated by Krakow’s cathedral and castle and I was keen to see both. I had suffered enough doom and gloom the previous day so I was hoping to experience something that would lift my spirits. It would have been great, but it just didn’t happen and again the disparity between what is and what people would like to believe in just came back to bite me in the ass.

One of the main problems I had with Krakow is that for all that the Old Town has some spectacular sights – especially the Market Square and the Church of the Virgin Mary – the architecture is overwhelmingly Italianate in character. In some ways, it’s like being in Lucca or Pisa or Rome – or even Budapest. Architecturally, there is little in the Old Town that makes you want to shout ‘Wow! That’s pretty damned Polish!’ – and the buildings on the Wawel rock are very much of the same style. The cathedral has green copper spires that reminded me of Copenhagen and fairly minimalistic golden domes that were like parts of Helsinki’s Russian Orthodox Cathedral. Inside, the cathedral was dim, poky and with a multitude of side chapels, all filled with groups of Poles for whom Wawel has become a touchstone of the new Polish nationalism which has come along in the wake of joining the EU and co-hosting last year’s European Football Championships. For the first time since the early 1920’s or maybe even earlier, Poland is under the thrall of neither the Russians to the east or the Germans to the west and they are eyeing the future with renewed confidence.

Well, good for them, I guess, but I’m afraid that the buildings on Wawel did nothing for me really. A ragbag of architectural styles and a castle of which little of the original structure remains. Sorry Poland…..

I moved on into the Kazimierz district, just the other side of the Wawel rock and the home of the original Jewish ghetto in Krakow. Like a restaurant with no food, Kazimierz seems to be doing reasonably well considering that there are minimal numbers of Jews living there. The area gained some status due to the fact that Steven Spielberg filmed much of ‘Schindler’s List’ there in 1993 and there have been festivals and the reopening of synagogues and cultural centres designed to renew Kazimierz’s Jewish heritage. It’s a scruffy area with narrow car-choked streets and a good deal of ‘yuppie-fication’ going on; signs advertising the sale of apartments in both Polish & English – in 10 years you won’t recognise the place. Even so, ‘Fascist Krakow’ stickers adorn some of the lamp-posts and anti-Jewish graffiti has been inadequately painted over at the rear of one of the synagogues. No wonder most of the survivors opted to go elsewhere at the end of the War.

It was time to go home. A cab ride through prosperous-looking suburbs took me out to the airport the following lunchtime. Krakow Airport is unequal to dealing with more than a handful of flights every day – the queues for the EasyJet check in were ridiculous because we were all in the queue for the Belfast flight, unable – due to poor ergonomics and design – to see that the lane for the Bristol flight was completely empty.

I dozed my way across Germany and the North Sea coastline, vaguely considering that I would soon be home and able to discuss what I had seen with someone at least. On the whole, Berlin had been great, Krakow a bit of a disappointment and Auschwitz completely overwhelming. I wish that I’d had some company but things don’t always work out the way you’d hoped.

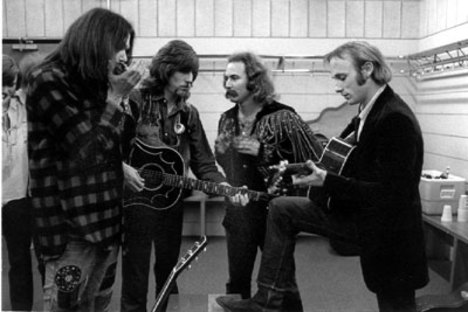

CSNY in 1970 – falling apart before they ever really got together

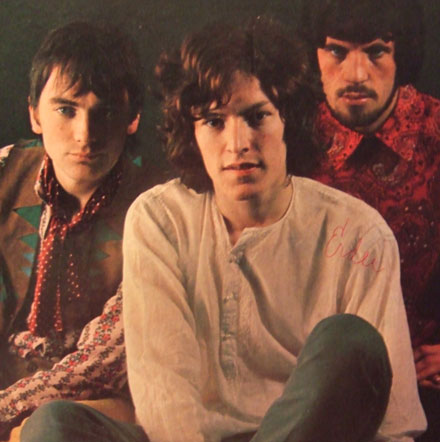

CSNY in 1970 – falling apart before they ever really got together Traffic in 1970; (L-R) Wood, Winwood & Capaldi

Traffic in 1970; (L-R) Wood, Winwood & Capaldi